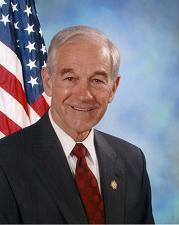

Ron Paul Quotes.com

2003 Ron Paul Chapter 31

6 March 2003

Home Page Contents

Congressional Record Cached

Not linked on Ron Paul’s Congressional website.

|

Ron Paul Quotes.com 2003 Ron Paul Chapter 31 6 March 2003 Home Page Contents Congressional Record Cached Not linked on Ron Paul’s Congressional website. |